Dosier: Poesía, poéticas y estéticas de la canción popular

Main Article Content

Abstract

The study of the relationship of the musical and the literary requires taking on an awareness of the complexity of confronting on object of study that, in many cases, escapes the conventions of the academic disciplines of literary studies and musicology. The lyrics of a song, as a point of encounter between the poetic and the sonic-musical and performative-vocal, seems to defy the idea of disciplinary belonging. A song’s lyrics can be understood as an autonomous media that participates in the literary, the musical, and the performative, but they do not necessarily limit themselves to any one of these frameworks in order to make sense as an aesthetic object, or for that matter, as an object of analysis. As Florencia Garramuño (205) indicates, “Some transformations of contemporary aesthetics foster modes of organizing the sensible that put into crisis ideas of belonging, specificity, and autonomy” (13).

It is precisely this crisis of the idea of belonging that permits us to consider a song’s lyrics as an autonomous media, or as named by Juan Miguel González Martínez (1999), operating from the field of musical semiotics a heterosemiotic phenomenon, that is, an artistic reality that is characterized by its multiple nature wherein semiotic codes from literature and from music interact, creating a third reality which is no longer subject to the semiotic frameworks in which it originates, and which requires the establishment of an interdisciplinary theoretical-methodological approach for its analysis.

If a song’s lyrics can stand out for their literariness or their poeticity, they nevertheless do not exclusively depend on a written dimension to make sense. Nor does poetry—the closest literary relative—depend solely on textuality to be approached, since beyond romantically metaphorizing the quality of a poem with adjectives like the song or music of poetry, poetic texts indeed possess a sonic dimension which is produced at the phonological level and is composed of rhythmic clauses, intonations, pronunciations, and, in the case of metrical poetry, meter, rhyme, and literary devices that affect their sonority. Likewise, if we assume that addressing song lyrics only requires us to turn to the musical realm, and that their meaning is expressed solely in the sonic dimension, we fall into a reductionism that overlooks the semantic and syntactic richness that comes from the textual dimension.

The problem becomes even more complex, from a methodological perspective, when we deal with artistic creations that arise in a hybrid zone, in-between disciplinary margins, as is the case of, for example, the musicalization of poems, or sound poetry. In addition to this, we can add, the implications of the sensorial, psychological and intellectual reception of music, as identified by Jean-Luc Nancy, for whom the act of listening to music necessitates the lister to take on a particular sensible and intellectual disposition, to most comprehensively apprehend the content and possible meanings of a work (279).

Additionally, the notions of the poetics and aesthetics of popular music permit us to establish relationships between the song as aesthetic object and other dimensions in which the literary or the musical are always immersed: social, political and cultural contexts. In this sense, the exploration of the cooperation between poetry and music in the shaping of new musical and poetic forms and genres becomes especially important—especially with respect to the ways in which musical poetics illustrate collective identities within their territories, being influenced by and influencing the ethos that defines their cultures, and expressing the friction, and often the discontent, between artistic expression and dominant social and economic policies.

In this context, this special issue creates a space in which to consider the relationship between popular music, poetry, the poetics and aesthetics, in a manner that makes full use of different approaches and methodologies, which taken together, offer us a rich view of the complex interactions between the musical, the performative, and the textual-literary in a contemporary context. In employing multiple conceptualizations of the discursive framework of popular song, this special issue explores a series of poetical-musical manifestations, problematizing the relationship of these musical creations with contemporary reality, historical memory, and the socio-political particularities of their territories. This dossier has gathered articles with diverse approaches and theoretical perspectives, which engage with popular song in all its breadth, yet always from the perspective demanded by the musical-lyrical text itself.

This special issue opens with the article “‘El dolor, el Magnífico’: Fito Páez y la tristeza en el rock Argentino” by Mara Favoretto, which explores the theory of the “topos del triste”, developed by Melanie Plesch, highlighting the concept of “extraordinary sadness” as a recurring element in Argentine literature and music. The article proposes that this feeling is manifested, not only in folklore and in tango, but also in Argentine rock, especially in the work of Fito Páez. Páez’s lyrics reflect diverse forms of sadness and ways of confronting it, creating a musical space for the expression and transmission of profound emotions.

According to Favoretto, Páez shows how rock can deal with difficult human experiences, transforming them into expressions laden with deep poetic resonance. In this way, Favoretto proposes that Páez’s songs encapsulate and perpetuate the tradition of extraordinary sadness, offering a unique form of emotional and cultural connection in Argentine national identity. By employing ideas taken from affect theory, this article also examines how Páez’s songwriting deals with private pain, individual pain, as well as social and historical pain, making evident Páez’s profound and structural influence on Argentine culture, concluding that his work has not only renewed the musical language of his country, but also has contributed actively to the configuration of a collective sensibility that has been marked by memory, loss and hope.

The second article, “Oralities and Musicalities in Dialogue: Kalfu and the Musicalization of the Mapuche Poetry of Elicura Chihuailaf”, by Gabriel Meza, analyzes the musicalization of the poetry of Elicura Chihuailaf by Chilean band, Kalfu. For the author, Kalfu’s musicalization represents the culmination of a dialogical process between orality and musicality that is articulated in three stages: first, the orality and musicality inherent to the Mapuche oral tradition to which Chihuailaf’s poetry belongs; second, the textualization of this orality in Chihuailaf’s poetic work, where his personal voice merges with his ancestral heritage; and third, the sonic reconfiguration of these elements through Kalfu’s musicalization, which establishes an intercultural and multilingual dialogue between Mapudungun and Spanish. The article examines how this musicalization opens up an intermedial space uniting the spoken, written, and sung word, reflecting both Mapuche tradition and the particularities of Chihuailaf’s poetic voice, emphasizing the role of music as a bridge between cultures and traditions. In this context, Kalfu not only adapts Chihuailaf’s poetry but also amplifies its sonic and polyphonic dimensions, integrating diverse voices and musical genres that reflect the Mapuche worldview and its intercultural engagement with Chilean culture. From this perspective, Kalfu’s musicalization configures a space where traditions, languages, and artistic expressions converge, giving rise to a new form of sonic reinterpretation and circulation of Chihuailaf’s poetry that, in turn, engages with and intervenes in Chilean poetic and musical traditions.

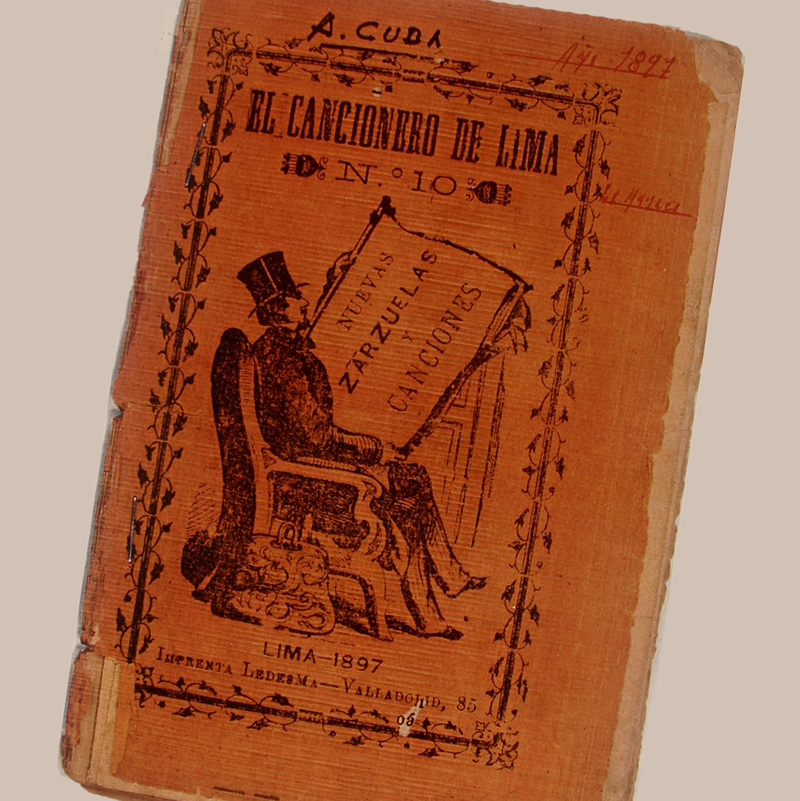

Third is Fred Rohner’s article, “Leer, copiar y crear. Estrategias poéticas en la composición de valses de la Guardia Vieja” which addresses Peruvian popular song through a novel study of the processes of literary appropriation present in the waltzes of Guardia Vieja artists. These processes reveal a complex relationship between reading and creation, in which the musicalization of poems does not merely reproduce texts but entails more sophisticated creative interventions, such as metrical, lexical, and structural adaptations. Rohner presents various examples of songs that intervene in the poetic texts that inspire them, including the case of the waltz “María”, which exemplifies this dynamic, through multiple versions of the song which engage with a poem by Juan de Arona. This demonstrates how musicians, composers, and other second authors re-signified and transformed literary material, turning it into autonomous works in the medium of popular song.

This practice reflects an active and direct circulation of cultivated poetry among popular music composers, who developed an alternative literary system outside the official canon, validating and re-creating poetic models within the popular sphere. The oralization of these texts, their adaptation to different social contexts, and their dissemination in collective spaces contributed to transforming literary discourse, moving beyond the notion of plagiarism and revealing a complex authorship that integrates production, consumption, and circulation. From this perspective, Rohner invites us to reconsider the relationship between vals peruano and modernist poetry, highlighting the need for critical studies that reconstruct textual versions and their histories, given the renewed interest in traditional canción criolla.

The fourth article, “‘I’m telling you things nobody wants to hear’: Pablo Chill-E, Chilean Trap & música urbana between Material Excess and Urban Realism”, by Israel Holas, explores the career of the Chilean trap and urban music artist Pablo Chill-E and how his work reflects the contradictions of contemporary Chile. The author proposes and develops this contradiction, demonstrating that, on the one hand, Pablo Chill-E fiercely criticizes Chile’s neoliberal present, which he characterizes as one marked by inequality and corruption, while, on the other hand, his music simultaneously glorifies individual entrepreneurship and materialistic consumption, aligning with the logic of capitalist realism developed by Mark Fisher. The article highlights how trap and urban music have transitioned from Chile’s geographic and socio-economic margins to become central to pop culture consumption. In this sense, Israel Holas argues that Pablo Chill-E’s music combines a materialistic aesthetic of excess with a visceral urban realism that exposes the failures of Chile’s neoliberal experiment and gives voice to marginalized communities. The article also examines how trap and música urbana in Chile are intimately tied to the urban peripheries of Santiago and to the illicit economies of the black market, which intensifies the idea of contradiction as a structuring element of his poetics and aesthetics. Finally, the article contends that Pablo Chill-E’s music, through its multiple discursive layers, offers a poetics of social critique directed at Chile’s socio-economic model, emphasizing violence, lack of opportunity, social marginalization, and widespread corruption, while simultaneously exhibiting an aesthetic of excess that flaunts materialist consumption and signals the economic potential of trap and música urbana as a way of escaping marginalization.

Finally, the last article of this dossier, entitled “Los Bunkers: Neoliberalism and Postmodernity in the Songs ‘Sabes que…’ and ‘Deudas’” by Julio Uribe, focuses on clarifying how the Chilean band Los Bunkers uses its music to articulate a profound and poetic critique of the impact of the neoliberal model on post-dictatorship Chilean society. Analyzing the songs “Sabes que…” and “Deudas”, the article demonstrates how Los Bunkers construct narratives that reflect the daily experiences and struggles of the working class—economic precarity, social abandonment of the elderly, the debt trap, among others—employing lyrical language that is open to multiple interpretations. Furthermore, the article emphasizes how Los Bunkers integrate poetic codes and musicalization that enhance emotional connection with their audience, transforming their songs into spaces of cultural denunciation that question the normalization of consumerism, competition, and economic deregulation in Chile. The article also explores the symbolic and audiovisual dimensions of their music videos, showing how these emphasize the social critique communicated in the song lyrics, positioning the band as a significant voice in expressing the social tensions of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

In conclusion, as editors, we are pleased to present this dossier and the voices brought together within it, as it testifies to the interdisciplinary work that is gradually becoming more visible among scholars from fields such as musicology, literature, and other related areas whose common object of study is popular song. For this reason, we express our gratitude to Contrapulso for welcoming this work, and we hope that through this dossier, readers may feel inspired to explore new ways of approaching the complexity and creative richness of popular song in its diverse connections with other contexts and disciplines.

Downloads

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.